INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Modern research increasingly relies on interdisciplinary collaboration, cutting-edge technologies, and efficient utilization of specialized expertise across multiple domains.1,2 These resources, while essential, often entail high costs and logistical complexity, particularly for institutions with broad research footprints and diverse scientific demands. Research institutions have strategically invested in developing shared research resources (SRRs; or core facilities).3 SRRs foster innovation and maximize research impact while enhancing economic efficiency by reducing redundancy in equipment procurement, staffing, and operating expenditures associated with maintaining and managing high-end scientific resources and training.2,4

Originally developed to support an institution’s investigators, SRRs may also provide access to external investigator users.5 This model offers scalability, accessibility, and long-term sustainability that exceed the capabilities of individual laboratories.6 The SRR operating model allows for the development of standard and customized services, enabling scientific advancement, nurturing collaboration, and encouraging operational optimization and fiscal responsibility.6,7 Since World War II, the federal government has supported research infrastructure in the United States by funding research ideas and negotiating indirect cost rates to support overhead costs at research institutions.8 This sustained investment has enabled the development of SRRs, institutional capacity, and translational pipelines. This funding support for research has positioned the United States as a leader in scientific discovery, disease treatment, and technological innovation. The impact of federal funding cuts on research and policy could significantly shift how SRRS supports research across Institutions.

IMPACT OF FEDERAL FUNDING CUTS ON RESEARCH AND SRRs

Recent executive actions by the Federal government have included pausing several federal funding streams for research, halting the disbursement of federal financial assistance, and directing agencies to review pending grants for compliance and performance.9–11 In parallel, additional directives have targeted diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives within federal programs and research focused on health disparities, specific populations (ex, women only, people with disabilities, people of color, etc.), community engagement, and workforce development.12 Collectively, these actions pose a significant threat to the financial and operational scaffolding that research institutions rely on to sustain collaborative infrastructure, particularly SRRS. These units often serve as the connection across departments and disciplines, enabling innovation, training, and research at large across many different disciplines.10,13,14 Disruptions to funding and strategic mandate risk destabilizing the very systems designed to support scalable, cross-cutting research efforts.

The February 2025 NOT-OD-25-068 guidance, which would cap indirect cost rates at 15% across all NIH grants, was most concerning to research organizations. This announcement was a significant deviation from the long-standing practice of negotiating institution-specific rates that support research organizations’ overhead costs and range, on average, between 30 and 70%, depending on the institution and its negotiated agreement with the federal government.9

Institutional Research Oversight

Across the United States, countless institutions facilitate research, but the differences in how research is supported, managed, and resourced can be striking to the average individual. No two organizations are structured or operate in the same way. Each reflects its own culture, leadership model, and operational priorities. Despite this diversity, all federally funded research institutions must adhere to the same overarching regulations, compliance standards, and mandates set by the federal government; how they are operationalized varies widely.15

Some institutions centralize oversight through robust research administration offices and streamline compliance, budgeting, and reporting under unified systems. Other organizations operate under more decentralized models, in which divisions or departments retain autonomy over certain research practices. These methods are adopted and adapted over time due to changes in growth, historical practices, funding portfolio size, leadership, strategic priorities, recruitment into new scientific disciplines, and the degree of integration across their own systems.16

The recent executive actions and proposed changes to federal research funding mechanisms could significantly disrupt scientific advancement and research infrastructure. Such changes will undeniably impact SRRs. As research funding becomes more constrained, some institutions may view SRRs as an attractive way to enhance their ability to secure new funding.15 Others may be forced to scale back institutional research support, reducing or eliminating SRRs. This study was designed to take the pulse of a broad range of institutions, attempting to understand the current climate and responses within them.

METHODS

This study was conducted utilizing a hybridized focus group and quasi-survey method. It was facilitated during a conference session at the Association for Biomolecular Resource Facilities (ABRF) Conference, held in Las Vegas, Nevada, on March 25, 2025. ABRF conferences provide a platform for SRR staff, directors, and administrators from across the United States to convene annually to collaborate on new technology development and emerging challenges and ideas related to the management and oversight of SRRs.

Association of Biomolecular Resource Facilities (ABRF)

The Association of Biomolecular Resource Facilities (ABRF) is an international association dedicated to supporting personnel, directors, staff, and administrators in SRRs for over 40 years. As the model for research support undergoes dramatic changes, each institution will develop unique approaches to prioritizing research operations that best leverage its scientific strengths. How these changes impact SRRs remains uncertain. The members of ABRF are those most affected by these changes and, therefore, an ideal study group for this study.

Recruitment

Volunteers to help facilitate focus group tables were recruited from the ABRF list serv, and a training session was held to help those facilitators understand the methods required for this study. Additional notetakers were seated at each focus group table as facilitators asked the questions and ensured participants stayed on topic.

The conference organizers invited participants to attend this session. The session was capped at 240 people, or 24 tables, with 8 participants, 1 notetaker, and 1 facilitator per table.

Study Design

Before the ABRF Conference, members were contacted through the ABRF online community and asked to share their current concerns about the proposed changes to Federal funding from the Executive Branch. All responses were qualitatively analyzed and coded into eight thematic areas and four prompts for each theme, which guided the study.

The eight themes developed were:

-

Institutional Policies

-

Recruitment Policies and Resource Duplication

-

Communication

-

Reorganization of Services

-

External and Alternative Revenue Sources

-

Value Proposition and ROI

-

Multi-Institutional Collaborations

-

Research Mission Alignment with Institutional Strategy

To facilitate discussion around each of the themes, four prompts were developed that could be used as discussion prompts

- What are some practical recommendations for enhancing [theme]?

- Why might these ideas succeed or fail within your institution or organization?

- What has your experience been in attempting to improve [theme]?

- How do you anticipate these changes will be perceived, given the current research climate?

- What key factors must be in place for these changes to occur within your organization?

- Have you employed any specific management frameworks to support these efforts?

- How do you navigate the human element of these changes?

- How have these shifts impacted you as a leader and an individual?

Two of the eight themes were randomly assigned to a table. Twenty-four tables were set up, assigning each theme to three tables. Participants were asked to sit at any table, without knowing which theme was assigned to them. The Investigator of this study led the session and kept time. Time was allowed to answer demographic questions, two scale-based questions, and one open-ended question. Participants were then given 25 minutes to discuss four prompts for each theme.

Data Collection

Facilitators guided the discussions, while designated notetakers recorded responses manually in notebooks that were distributed and collected by the Investigator of this study. Slido© (Webex by Cisco), an interactive polling software application, collected high-level demographic information about the participants. This information included the type of research organization, their role within it, and the years of experience in that role. Slido© was also used to collect responses from participants who felt uncomfortable sharing their thoughts aloud at the focus group table.

Ethical Considerations

The Institutional Review Board at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center provided protocol review and approval for this study. Participants provided informed consent verbally after being advised of the study risks, benefits, intent, and data use. Participants were explicitly informed of their rights, including the right to abstain from any topic, withdraw at any point, and expect anonymity in reporting results. Emphasis was placed on mutual respect, privacy, and voluntary participation.

Data Analysis

Slido’s© information and detailed notes from each focus group were systematically collated and organized by theme. The qualitative data from focus group discussions were coded to identify emerging themes, key insights, and significant participant quotes.

In addition, profiled information collected through Slido© was subjected to quantitative analysis using Excel’s statistical methods. This analysis enabled the identification of patterns and trends in the participant profiles.

Findings from this study are reported based on the integrated analysis of qualitative and quantitative data, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of participant perspectives and overarching themes.

RESULTS

Demographics

In total, 226 participants (including facilitators and notetakers) participated in the focus group session. Individuals who worked in academic (75%), nonprofit (21%), and industry (5%) in Administrator (34%), Director (26%), Manager (17%), Staff Member (14%), and Business roles (10%) were present in the session (Table 1). Experience with SRR(s) ranged from 0 to 15+ years, with a mean of 6.6 years across all participants.

General Outlook on Federal Funding and Guidance Changes

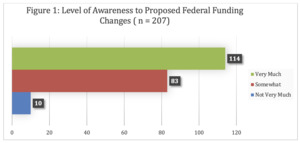

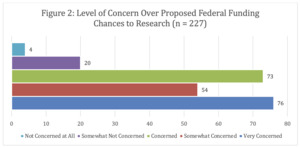

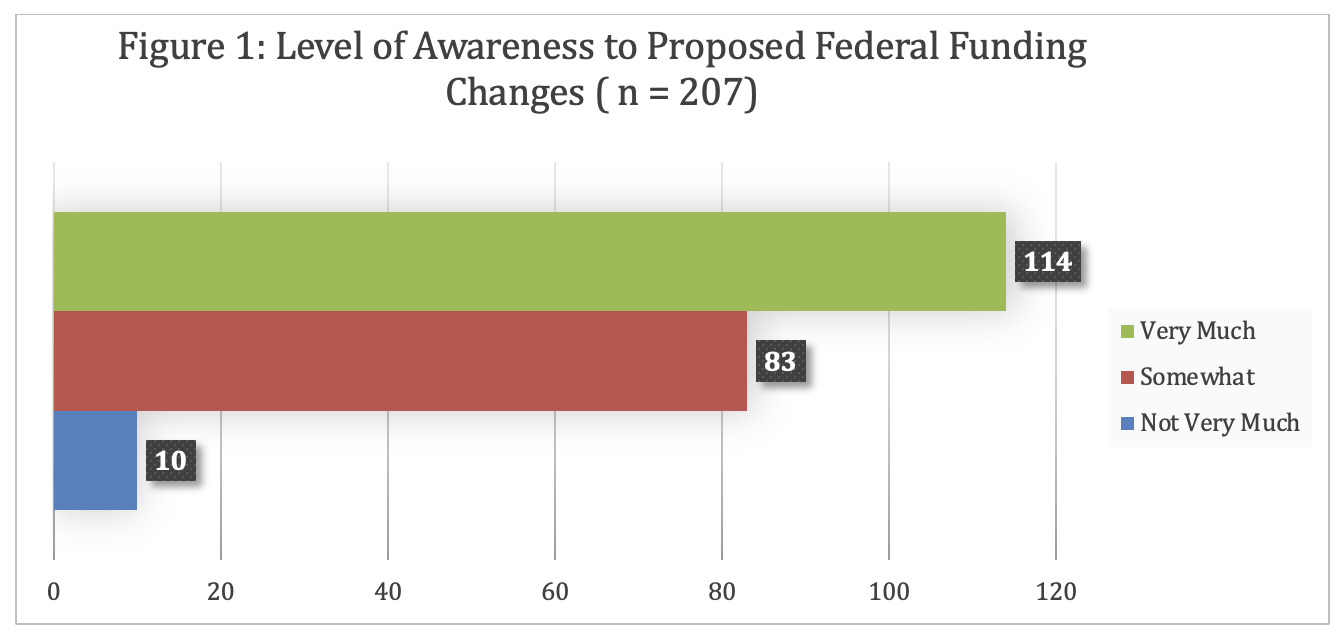

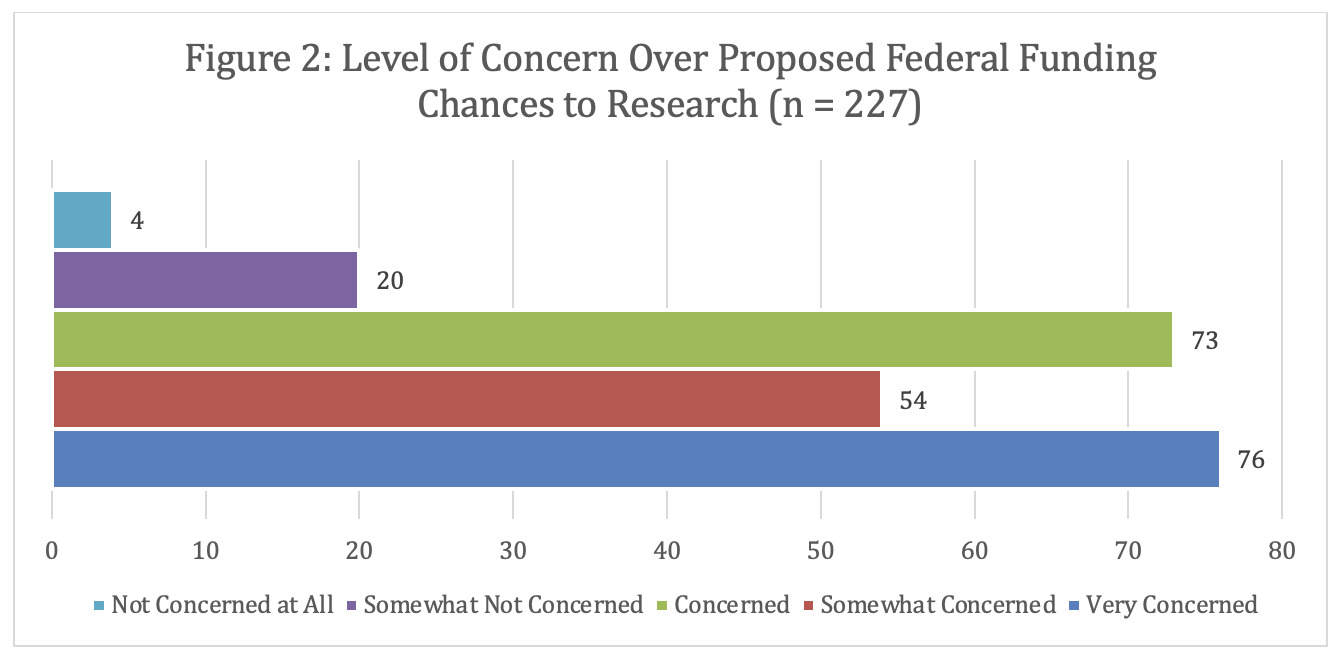

After collecting participant profile information, the participants were asked two qualitative questions: 1) How aware are you of the recent executive actions and how they could impact SRRs? 2) How concerned are you about the proposed federal funding changes? Most participants rated on a scale of 1 to 5 that they were very aware of the proposed changes (Figure 1), and most participants indicated that they were very concerned about the proposed changes (Figure 2). This information assured us that individuals in the room had context and awareness of Federal research funding and guidance changes, making this study’s results meaningful.

Reported Concerns on Federal Changes to Research and Funding

A final question was posed to allow participants to comment on specific areas of concern regarding the Federal changes. This was facilitated as an open-ended question and collected in Slido©. The findings (Table 2) indicate that Indirect Rates are the primary concern, followed by NIH/NSF funding cuts to research, DEI Program elimination, Federal Administration and Legal Actions, and finally, the impact of Tariffs, Endowment taxes, and Global Science.

FOCUS GROUP FINDINGS BY THEME

Focus group discussions surfaced a wide range of insights spanning institutional culture, operational infrastructure, leadership dynamics, communication practices, and organizational barriers. The diversity in how research organizations are structured and function revealed the complexity of participants’ roles and the varied institutional contexts in which they operate. Given the breadth of findings, this section focuses on a subset of themes most relevant to supporting Shared Research Resources (SRRs) across institutional models.

Institutional Policies

The most significant concerns among SRR leaders and staff were indirect cost caps, NIH/NSF funding cuts, legal/visa barriers, and DEI rollbacks. These four areas of concern tie directly into shifts in policy and support for federal funding, foreign influence, and DEI. As a result, SRRs felt an urgency for institutions to diversify their funding sources by seeking out more industry and philanthropic resources, which could better help to position their organizations to weather these changes. In addition, a need for more substantial institutional leadership alignment and engagement practices, including SRR representation at the table, was seen as essential to facilitate operational decisions that would impact researchers. SRR staff are uniquely positioned because they work with researchers and administrators daily. These relationships allow organizations to leverage their embedded expertise and perspectives to help develop a resilient, adaptive framework that supports Shared Research Resources (SRRs) and the institution.

The need for Institutional policies to increase the visible value of SRRs in facilitating and supporting research pipelines, and the need to develop stronger operational efficiency to support SRRs, were widely discussed across groups. To support the long-term sustainability of SRRs, institutions must define and promote their fundamental purpose and mission. Acknowledging the efficiencies enabled by a shared SRR infrastructure across a research enterprise allows institutions (both leaders and researchers) to be nimbler with their dollars and more adaptable across their workforce and resources. Creating operational efficiencies through shared infrastructure, streamlined procurement, and centralized processes without excessive bureaucracy will help protect these intellectual hubs and ensure resilience to support SRR resources and the institution’s research.

Recruitment Policies and Duplication of Resources

Concerns emerged around institutional policies related to 1) recruitment of faculty and staff to work in SRRS and 2) decision-making processes for purchasing new resources and equipment. SRRs expressed worry about their ability to recruit new personnel to work in SRRs and replace faculty and staff who may depart due to fear or uncertainty, considering federal funding cuts. These reductions pose a significant threat to recruiting and retaining skilled scientific staff and faculty, compounding existing challenges in training individuals to operate specialized technologies. Challenges in recruiting highly specialized faculty and staff underscore the need for succession planning, standardized hiring policies, and strategies to mitigate turnover risk.

In parallel, many stakeholders emphasized the importance of aligning decision-making processes with policy. For example, centralizing equipment purchasing practices to minimize duplication across research enterprises. There was a clear call to standardize institutional policies across recruitment and resource acquisition to support more efficient, transparent decision-making. SRRs strongly advocated for institutional leadership to take ownership of these efforts with stakeholders’ buy-in, recognizing that such system-wide coordination falls beyond the operational scope of individual core facilities or the departments within many reside and is a necessary initiative that requires the collective effort of many stakeholders.

Communication

Focus group participants emphasized persistent breakdowns in institutional communication, revealing a critical gap in leadership strategies. Through multiple discussions, the need for honest, consistent, and inclusive communication practices was repeatedly identified. Many staff and SRR directors described the lack of clear, centralized, and transparent messaging from leadership, which contributed to rising stress, mistrust, and operational inefficiencies.

Given the current challenges with federal and institutional messaging, some participants noted that their institutions have held town halls, conducted feedback surveys, and sent email updates to improve engagement. However, there was a strong call for more meaningful, bottom-up, two-way communication channels and safe spaces where SRRs, faculty, and staff can share concerns and receive timely, responsive feedback. Participants emphasized that such mechanisms would reduce anxiety and help administrators stay grounded in the realities of the scientific workforce by actively listening to those closest to the work.

Reorganization of Services

Focus group participants shared valuable insights and discussed recent efforts to reorganize and centralize SRRs to enhance efficiency, reduce redundancy, and eliminate the high costs of overseeing high-end equipment. However, few participants acknowledged that their organizations have actually or fully executed these plans. While the benefits of shared governance and unified systems can boost efficiency, it must be collaborative. Participants acknowledged and identified significant challenges, with ideas to reorganize or centralize services to improve efficiency. These included cultural resistance, fear of losing departmental autonomy, protectionist behaviors, and institutional reluctance to invest in the infrastructure necessary to support these initiatives.

Participants emphasized that centralization is not a burden for administration to take on alone, but requires strategic input from personnel, investment in infrastructure, and a communication strategy to be effective. Effective reorganization requires investment in operational support systems, including IT infrastructure, space allocation, HR policies, and compliance frameworks, to ensure long-term success. Success depends on critical alignment with leadership’s support and commitment to fostering institutional collaboration, pooling resources, and minimizing duplication. Equally important is ensuring that researchers retain access to scientific instrumentation and that oversight structures are thoughtfully aligned with the needs of the research enterprise.

External and Alternative Revenue Sources

Focus group participants examined the opportunities and challenges of generating external and alternative revenue for SRRs. While institutions are experimenting with various approaches, such as industry partnerships, philanthropy, and revised pricing structures, institutional barriers remain significant. To facilitate external relationships, many participants expressed having obstacles and a lack of support for marketing and outreach, contract negotiation, and grant development to foster external growth. Participants also frequently cited legal contracts, compliance requirements, and institutional bureaucracy, especially around MTAs and MOUs, as significant barriers to external partnerships. Slow administrative processes and limited support for streamlining these agreements hinder efforts to build relationships that could generate alternative revenue. SRRS needs to develop stronger alliances with institutional business partners to advance SRR’s strategic goals.

Concerns also emerged regarding the potential impact of external revenue generation on internal service users, particularly perceived (even if not real) presumptive service delays and reprioritizations, which can lead to tension. Participants highlighted the tension between serving home institutions and expanding to external users. These insights indicate the need for coordinated institutional strategies that facilitate external engagement while preserving internal equity and scientific mission. While participants recognized the importance of expanding external funding, they acknowledged the administrative burdens, including legal, cultural, and organizational complexities, that must be carefully navigated to realize these opportunities.

Value Proposition and ROI

Focus group participants strongly advocated a cultural shift in how SRRs are perceived. SRRs expressed concern that research stakeholders continue to view them primarily as transactional service units, rather than recognizing their essential role as collaborators and knowledge partners in scientific innovation, training, and discovery. Institutional leaders often rely on metrics that fail to capture the full scope of value SRRs contribute to research organizations.17 These limited indicators overlook the intellectual collaboration, training, innovation, and infrastructure support that SRRs provide, which are essential to sustaining a competitive and inclusive research enterprise.

In today’s evolving research climate, SRRs are calling for a redefinition of return on investment (ROI) metrics—ones that incorporate both qualitative (e.g., contributions to recruitment, collaboration, educational initiatives, and innovation) and quantitative (e.g., publications, grants, financial performance, usage, etc.) indicators to more fully capture their contributions to scientific innovation, training, and institutional success.5 Many of these contributions, such as intellectual collaboration, mentorship, and infrastructure support, often go uncredited under traditional evaluation frameworks. Tracking these elements remains challenging, however, due to inconsistent documentation practices and processes that fail to account for the unique operational realities of SRRs.

Multi-Institutional Collaboration: Opportunities and Barriers

Focus group participants underscored the growing importance of multi-institutional collaboration as a strategic response to tightening budgets and workforce constraints in the research environment. These partnerships hold considerable promise for driving innovation, enhancing operational efficiency, and supporting the long-term sustainability of SRRs. Key strategies include building SRR networks across institutions to improve accessibility and reduce duplication, consolidating high-end equipment to foster integrated research ecosystems, and engaging with external funding sources beyond traditional federal agencies such as NIH and NSF. Financial sustainability in this context requires innovative approaches, including reciprocal pricing mechanisms, centralized grant structures, and business incubator initiatives to attract external clients and investment. At the workforce level, cross-training and shared staffing models were noted as practical tools for building adaptability and continuity. At the same time, advisory committees are vital in shaping policy and guiding implementation.

Despite their potential, participants expressed frustration with implementation challenges stemming from administrative and legal barriers. Like issues addressed in supporting collaboration with external resources and alternate funding, Institutional silos, such as disjointed IT, HR, and contracting systems, complicate collaboration. At the same time, rigid compliance requirements, reciprocal pricing limitations, and export control concerns inhibit transparency and resource sharing. To overcome these hurdles, participants called for streamlined governance and administrative frameworks. They envisioned centralized infrastructure platforms, harmonized agreements (e.g., MOUs), and cross-institutional strategic planning to facilitate seamless engagement.

Research Mission Alignment with Institutional Strategy

Focus group discussions reveal a growing consensus on the need to clarify and elevate SRRS’s mission as a vital engine of discovery, education, and institutional advancement. This need for clarification centers on the dual identity of SRRs: their operational role in service provision and their intellectual contributions to scientific collaboration and innovation. The tension created by this dual role reflects broader institutional narratives in which SRRs are often perceived as “internal vendors” rather than embedded research partners. The resulting disconnect undermines the scientific impact and limits opportunities for deeper integration into an institution’s research mission and strategic planning. Participants emphasized that the success of SRRs depends on operational excellence and strategic alignment with institutional priorities.

To develop a better alignment, SRR leaders who have a place at the table, be in advisory roles, and positions where decisions are being made, help to ensure SRR knowledge and goals are integrated into research planning. Strong administrative support, visibility within organizational structures, and integration into the broader academic mission emerged as key factors in enabling SRRs to thrive. Without such support, many SRRs remain institutionally invisible, hampering advocacy for funding and limiting their contributions as centers of collaborative innovation. Rethinking how SRRs are positioned and reframing them as intellectual and educational partners, rather than service units within the research mission, can provide institutions with greater leverage to reach their potential while advancing their missions of research excellence and training the next generation of scientific leaders.

DISCUSSION

SRRs face amplified systemic stress, especially with frequent federal funding and research policy adjustments. The solutions many SRRs seek require coordinated leadership and strategic planning, which focus on working together to prioritize efficiency and on how decisions are made, with an eye towards equity and/or SRR representation. Many cross-cutting themes emerged as the focus groups discussed the selected topics. This resulted in several recommendations that offer a framework for Institutional engagement and operational resilience.

Recommendations for Managing and Mitigating Federal Changes: A Shared Research Resources (SRR) Perspective

-

Strategic Integration and Leadership Engagement

-

Institutions are encouraged to engage SRR leadership in strategic planning by establishing formal opportunities for SRR leaders to actively contribute to planning processes and decision-making. The operational expertise of SSR leadership is critical to shaping decisions that directly impact research infrastructure. SRR Directors serve as key conduits, facilitating the bidirectional flow of information between administration and research teams and are uniquely positioned to identify system-level risks and opportunities.18

-

SRR leaders integrated into institution-wide oversight activities can support decisions, including equipment procurement, space planning, IT infrastructure roadmaps, policy development, and the selection of centralized management systems such as billing and reporting. Their involvement helps reduce redundancy, identify opportunities, improve operational efficiency, and ensure that infrastructure decisions are aligned with the evolving needs of the research community.18

-

-

Collaboration and External Engagement

-

Institutions are encouraged to remove legal barriers and develop standardized templates and policies that offer a clear, consistent framework for engaging with external partners. Integrating and facilitating external funding sources into SSR revenue enhances financial resilience and sustainability. Efficient workflows and policies are essential for supporting external partnership opportunities such as academic reciprocity agreements and industry service requests. Workflows may include operational partnerships between SSRs, leadership, legal, and IT. Accessible frameworks enable SRRs to respond nimbly to collaboration opportunities and reduce service delivery delays.

-

Institutions are encouraged to advance multi-institutional collaborations, establish reciprocity agreements, and pursue strategic opportunities with industry partners. Establishing core facility networks across academic institutions allows for shared access to high-cost equipment, streamlined service delivery, and reduced redundancy. Institutions can avoid duplicative capital investments by pooling resources and jointly pursuing large-scale funding opportunities. Clear governance structures and harmonized administrative protocols—such as memoranda of understanding (MOUs) and shared grant mechanisms—enable smooth and sustainable inter-institutional engagement. Appropriate administrative support to attract and maintain industry partnerships is critical, leveraging excess SSR capacity to maximize revenue.13

-

-

Operational Efficiency and Resource Optimization

-

Organizations can help foster and establish internal SRR working groups. Cross-functional teams within SRRs can be tasked with exploring cross-training, lean management strategies, bundled service contracts, and other operational activities. Discussions can foster processes to remove redundancy from resources and generate process improvement insights to help improve efficiency across the organization.

-

Institutions champion and support the implementation of standardized business operating procedures that ensure consistent, centralized protocols for SRR operations to better address needs. Standardized operations enable improvements in reporting, reduced red tape, centralized processes, greater accountability, and stronger alignment with institutional leadership. Accessing consistent, accurate information from the same source helps everyone make more nimble collective decisions.19

-

Partnerships between SSRs, procurement, and facilities support developing comprehensive equipment listings and tracking tools. Processes need to be sufficiently robust to identify redundancy and generate utilization metrics that will inform strategic decommissioning and replacement of instruments. For example, shared, walk-up instrumentation hubs can be considered to reduce small equipment purchases. These procedures can also be applied to software licenses, operating systems, and tools used across the organization.17

-

Leverage Institutional policies and digital tools to ensure SRRs are tagged in grant submissions, provided appropriate grant budget guidance, notified of funded awards involving SRR services, and appropriately acknowledged or cited in resulting publications and reports.20

-

-

Visibility, Recognition, and Funding Alignment

-

Institutions can advance and communicate the value proposition of SRRs. A cultural shift is needed to reposition Shared Research Resources (SRRs) as intellectual collaborators rather than transactional service units. Institutions are encouraged to invest in measuring and communicating SRR impact using qualitative and quantitative metrics—such as contributions to recruitment, innovation, publications, grant funding, and career development. Strategic marketing, case studies, and visual storytelling can be leveraged to elevate SRR visibility, foster institutional recognition, and strengthen long-term support.

-

Institutions can support SRR workforce development by implementing intentional cross-training programs, core career ladders, shared staffing models, and structured mentorship policies within SRRs. These programs bolster infrastructure resilience and operational flexibility during hiring freezes, staffing reductions, or other constrained circumstances. Maintaining core functionality and preserving research quality through a resilient workforce is essential to sustaining high-impact research environments. Development and maintenance of core talent can be the backbone of these efforts.21

-

This analysis highlights a dynamic, evolving research landscape in which SRRs must strategically position themselves to meet growing institutional demands and fiscal pressures. By prioritizing cross-institutional collaboration, streamlining administrative and legal frameworks, engaging leadership, diversifying funding models, and investing in workforce development, institutions can strengthen SRR sustainability and unlock their full potential as collaborative, innovative, and mission-aligned components of the research enterprise. As federal support fluctuates and operational demands intensify, adopting these strategies will empower institutions to remain resilient, resourceful, and competitive in advancing scientific discovery and education.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors of this paper would like to acknowledge the contributions of volunteers who stepped in to serve as moderators or note takers for the focus group sessions held at the ABRF Conference. These individuals are Justine Kigenyi, Ben Wright, Karolien Denef, McHugh, Alex Zevin, Nick Ambulos, Josh Rappaport, Joe Dragavon, Aaron Larson, Lena Schroeder, Amanda Koehne, Sarah McLeod, Selene Colon, Jennifer Koblinski, Andy Ott, Julie Auger, and Sheenah Mische.

We would also like to thank the ABRF Executive Director, Kenneth Schoppman, for supporting this research study and keeping us on track. The Association of Biomolecular Facilities facilitated this session during their conference.

Financial Statement / COI

No financial support was used to generate this work; the authors do not express any associations that may pose a conflict of interest. This work was approved by the Cincinnati Children’s Institutional Review Board. All subjects who participated in this study were given the requisite informed consent.